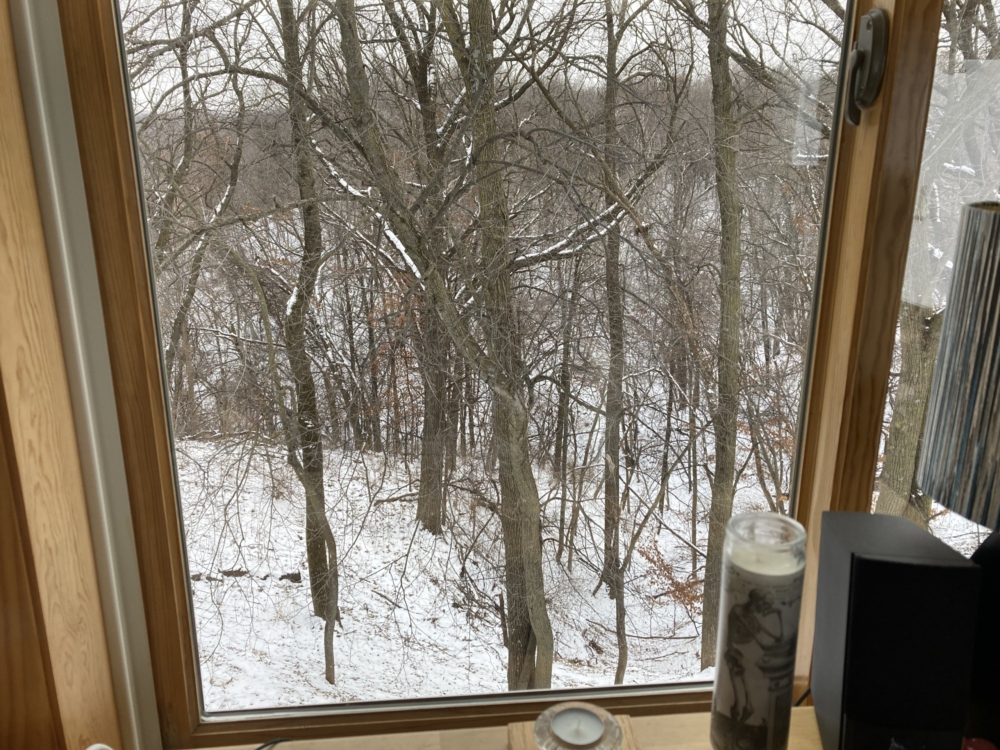

Behind our house is Hidden Valley Park, 45-acres, heavily wooded on steep ravines with the Credit River at the bottom. My desk in my office on the second floor is up against the window, allowing a view of trees, the steep drop-off, and the sky above. Even in winter the view is captivating. Margie’s office, on the first floor just below mine has a similar view. It’s one of the reasons we purchased this house and named it The House Between.

The view from my office window could be called a distraction. A distraction to my reading, planning, writing. Over the years, it’s consumed untold hours in leisurely watching, leading to discovery, wonder, and silence. In terms of productivity, it’s a distraction; in terms of spiritual acuity, it is one of the best things that has ever happened to me.

“Consider the ravens,” Jesus told his followers. He didn’t mean glance at them as they fly past. He said consider them. Consider that “they neither sow nor reap, they have neither storehouse nor barn, and yet God feeds them” (Luke 12:24). In other words, observe them as they live, learn how they feed, and ponder the implications for your life, values, and worldview. That is what consider the ravens means. This command suggests an obvious question for us: do we intentionally spend time and effort considering the ravens?

“Consider the lilies,” the Lord continues, “how they grow: they neither toil nor spin; yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these” (Luke 12:27). In other words, watch flowers over their full life cycle, from sprout to full plant to flower to wilting to seed and think through the glory they exhibit compared to Solomon’s greatest achievements. Considering birds and flowers, considering nature, considering God’s world takes unhurried watching, focus, quiet; it takes time, stillness. And again, this command suggests an obvious question for us: do we intentionally spend time and effort considering the lilies?

In sermons on these texts, I’ve heard what preachers believe we should conclude from considering ravens and lilies. Pretty much an expansion of Jesus’ own explanation. Never have I heard an acknowledgement that these are commands by Jesus to his followers. That we are commanded to actively consider nature. That there might be value in it. But after the months sitting in my office, I can attest to the fact that there is much more we can learn from ravens and lilies. And chickadees, juncos, finches, crows, falcons, nuthatches, deer, wild turkeys, red fox, owls, oaks, maples, lindens, spruce, and all the rest.

The same God who spoke in Jesus and in Scripture, has spoken in nature, the creative word. And in the stillness, I find myself near the Interface between the visible and invisible, where glimpses of glory and spiritual reality occasionally burst out. If, and when, that is, I have eyes to see.

In a society that prizes efficiency and productivity, stillness is underrated. A spiritual discipline, ancient poets and mystics understood it is where we come to know the One who reigns overall. The Hebrew psalmist expressed it beautifully (46:10).

“Be still, and know that I am God!

I am exalted among the nations,

I am exalted in the earth.”

Watch the unfolding of nature over succeeding seasons. There is such harmony and order, such intricate interrelationships. My little slice of nature in the woods does not exist in a vacuum, but is connected to the rest of nature, including me.

Eugene Peterson, in The Message, translates Psalm 46:10 this way:

“Step out of the traffic! Take a long,

loving look at me, your High God,

above politics, above everything.”

The poet, Wislawa Szymborska, in “Classified,” (Poems: New and Collected; Harcourt, 1998) touches on the same reality.

I TEACH silence

in all languages

through intensive examination of:

the starry sky,

the Sinanthropus’ jaws,

a grasshoppers hop,

an infant’s fingernails,

plankton

a snowflake.

How do I explain this?

I have learned much from watching our woods. The scolding calls the chickadees make when something displeases them. The tiny, high-pitched calls that seem to end with a question the goldfinches make from the branches of trees when they are peeved. The way deer can suddenly appear in a clearing and then with a few mincing steps disappear back into the trees. How pairs of wood ducks land on branches each spring and walk around searching for a place to nest. How murders of crows will swarm an owl, cawing incessantly, diving at them until they chase it away.

But all such knowledge, though wonderful, is not the primary thing. No mistake: I love learning about the creatures that are our neighbors and delight in it, wanting to learn more.

Still, when I am quiet, still, and looking, I realize I am the only creature in this diorama that is anxious and agitated about the future, about what tomorrow may bring. Politics, the economy, the cruelty of threats of mass deportations, the chaos. In contrast. the ravens, oaks, and goldfinches live in the moment, content to do what they were created for. They do get agitated when a predator shows up, of course. These seem momentary however, in the moment of danger, and after the predator departs contentment resumes. The contentment they display is what I want—I need—in myself. A contentment to live in a broken world following the calling of my Creator.

The Puritan divine, Jeremiah Burroughs, defined the deep wisdom I see in the woods and need in The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment (The Banner of Truth Trust; 1648; 1987; p. 19):

Christian contentment is that sweet, inward, quiet, gracious, frame of spirit, which freely submits to and delights in God’s wise and fatherly disposal in every condition.

My lack of contentment is not neutral, but an abject failure to trust. Or, more accurately, my perverse tendency to trust the wrong things. I’m anxious because I want to find a solution to things, which means I am trusting myself, others, leaders, whoever. I’m hoping that we can solve the world’s problems instead of relying on our God and his gospel in Christ. Our Old Testament reading (Jeremiah 17:5-10) in church on Sunday spoke to me—and this failure of mine—directly:

Thus says the Lord:

Cursed are those who trust in mere mortals

and make mere flesh their strength,

whose hearts turn away from the Lord.

They shall be like a shrub in the desert,

and shall not see when relief comes.

They shall live in the parched places of the wilderness,

in an uninhabited salt land.

Blessed are those who trust in the Lord,

whose trust is the Lord.

They shall be like a tree planted by water,

sending out its roots by the stream.

It shall not fear when heat comes,

and its leaves shall stay green;

in the year of drought it is not anxious,

and it does not cease to bear fruit.

The heart is devious above all else;

it is perverse—

who can understand it?

I the Lord test the mind

and search the heart,

to give to all according to their ways,

according to the fruit of their doings.

Learning stillness is a long process and I have just begun. Sometimes, in the stillness I’m surprised at a sliver of light, of glory, shining out to suggest there is far more to reality than matter and energy. Matter and energy are glorious, no mistake, but there is more. And in that moment my heart swells with wonder. And sometimes, in the stillness I’m taught by ravens and lilies about the bleakness, the lack of trust in my soul. And that, like them, we are accepted by God and invited into a deeper way of life. It’s a brief taste of the New Creation and is transforming.

Living in this reality changes how I see everything. I am better able to see people who disagree with me as precious, worthy of love and service. I am better able to see creation as God’s good gift of which I am called to be a steward, cultivating and caring for it tenderly. I am better able to know that God is exalted in all the earth. I am better able to know that even if rulers rage and scrolling implies doom, he is exalted among the nations.

Who knew? Turns out there is wisdom in the woods of Hidden Valley Park.

Photo credit: by the author with his iPhone.